Today, Project Management Academy® is proud to present the final chapter of its "Interview with a PMP Exam Prep Instructor" series. In previous segments, we absorbed a multitude of information about the Project Management Professional (PMP)® exam and gained some great project management insight earned through our instructors' combined 73 years of project management experience. In this final article, we will discuss their outlook on the project management field and give them an opportunity to share a few stories from their extensive careers. If you are new to the series, check out part I and part II. For a refresher on our instructors, they are:

- Gregg Richie, PMP, CNP, MCTS; 35 years of experience in construction, project and facilities management with 30 years of in-class instructor experience; author of Wiley Press' Official Microsoft Academic Course book on MS Project

- Jim Stewart, PMP, CSM; 20 years of experience in IT, financial, and pharmaceutical project management roles with 11 years of instructing experience

- Francis Mies, PMP; 18 years of experience in IT and telecommunications project management with over 15 years of instructor experience

7 Secrets to Passing the PMP Exam

Learn the secrets to passing the PMP® exam on your first try.

PMA: We were curious: what made you decide to teach PMP certification courses?

JS: I've been teaching since 1983 when I was an IT guy. I didn't choose to and I don't know that I had any calling in that direction. It's just that a forward-thinking boss recognized that I had the ability to explain complex, technical ideas in layman's terms. So I kept teaching right through my career shift to project manager. I don't know that the PMP certification training that I do was so much a decision as a natural progression.

GR: After the demise of the construction industry in 2008 it made perfect sense for me to begin teaching full time. I began teaching in 1983, received my degree in adult education in 1999, so the transition to a full-time instructor in 2009 made sense.

Now, the main rea

PMA: That's a powerful message. It's great to give back, but it's even better to get others to give back. So, in your experience, what one skill does a project manager need to succeed?

GR: Two words - professional communication. All project managers need to have communication skills, but they must also do it in a professional manner. A project manager can have a Master's degree in communication or be an expert in the English language, but that does not mean they can communicate professionally. Since 'professionalism' in my opinion is not a skill, it is a trait or characteristic, I would say the successful project manager knows how to communicate professionally, appropriately sending the right message, to the right audience, in the right format, across the most appropriate medium, at the appropriate time.

JS: For me it's perseverance. Giving up is not an option. I don't know that you have to be really smart to be a good PM. It doesn't hurt, I suppose. But this profession requires a certain determination to knock down walls in order to get things done. When I was a hiring manager, I always looked for the "git-r-done" person over the genius. If someone met both criteria, even better.

PMA: Perseverance and communication definitely extend well into any management role, and they certainly see their use in project management. Speaking of, what is your outlook for the project management industry in future years?

JS: Oh it's fantastic. I've been a PM for twenty years and have never really lacked for work. I may have a somewhat broader skill set because I teach, but I'm always being contacted by recruiters for short-term contracts. If you think about it, IT will always roll out new technology, buildings will always be built, and new drugs will always be produced. Someone has to drive those efforts. And more and more companies are looking at or using Agile. So there's now even more ways to be involved.

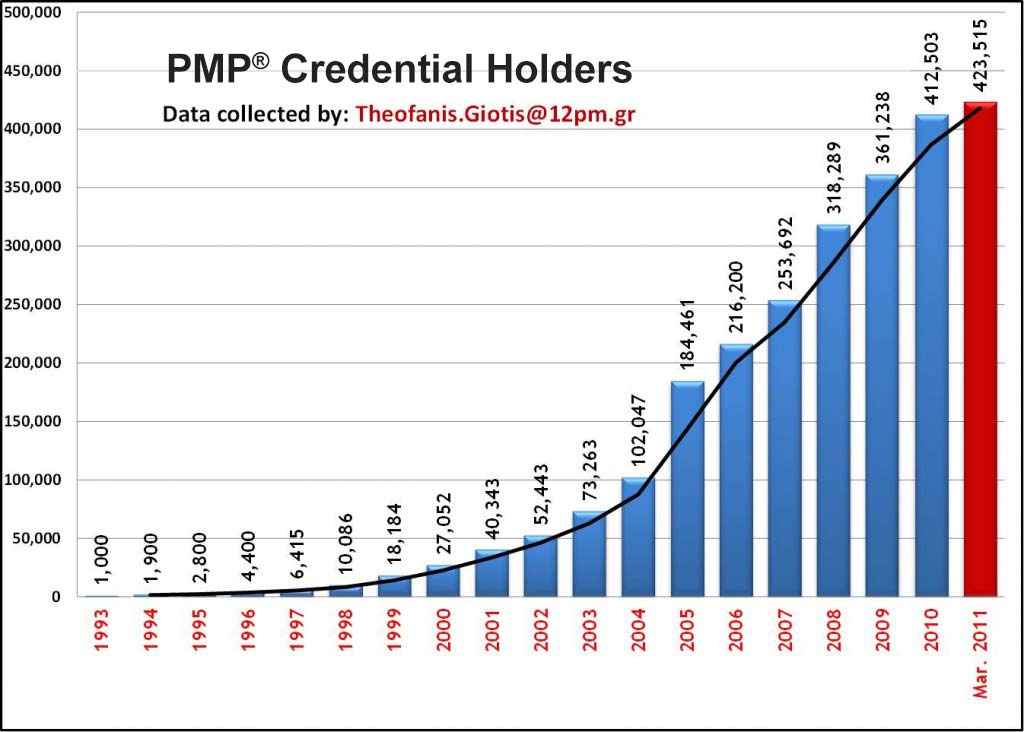

GR: With the increase in desirability for the PMP credential, the outlook for the project management profession is bright. Many industries are adopting project management as a primary approach to meeting strategic objectives. As long as PMP credential holders manage projects in a professional manner and bring credit to project management as a profession, our industry will continue to grow. We must not, however, allow ourselves to become so process-focused that we lose sight of the objective of each project, or worse, we lose sight of the people in the project. The more people-focused that PM's become, they will find that the 'process' becomes easier and in some cases, even takes care of itself.

FM: I think it will continue to expand. I can't envision any slowdown in the foreseeable future.

PMA: Great! Of course, we're all glad to hear that project management has a bright future. The next question is a little more arbitrary, so we'll give you a moment to think about it. Defined as a percentage or ratio, how much would you say a project manager's function relates to technical skill and how much relates to managerial skill?

FM: Obviously this can vary based on the type of project. I like to think that a PM doesn't have to know a lot about the technology, but on some projects that is not realistic. Having said that, I think that on routine type infrastructure projects the PM should have a 30%-70% ratio technical to managerial.

GR: If technical skill is defined as the ability of the project manager to be able to perform technical work on the project, like writing code for a software project, then I would say the requirement is 20% technical, 80% managerial.

We have undergone a paradigm shift in the project management world over the past 15 to 20 years. In the early days when I started in project management, the project manager had deep technical knowledge of the project. This means that not only did they know every aspect of the technical side but they also knew how to manage projects. Now, we realize that managing the project is different and separate from the technical side of the project, and professionally speaking, should maintain that separation and difference. However, this does not mean that the project manager can be totally ignorant of the technical side of the project. For example, I can barely spell IT, but I could manage an IT project, because I know how they go together. I don't know how to write code, but I know enough to discuss technical issues intelligently. In the best interest of professional project management, it is best to have a project manager with a PMP certification and who possesses enough knowledge of the technical side of the project to be aware of what is going on.

JS: If you had asked me that when I first started I would have said 80% technical, 20% managerial. Now I know better. This is a people job which is why PMI stresses soft skills so much. Anybody can learn how to use Microsoft Project. But the challenge comes in trying to motivate, inspire and lead people.

PMA: That was very insightful. The point about a people-oriented approach is an important one that often gets lost in translation, especially for students trying to sit for a technical exam like the PMP certification. Hopefully, this idea opens up discussion for our last question. Tell us about one of the more challenging projects you have been assigned to. What did it entail, and how did you handle the situation successfully?

FM: I was a contractor working for a large manufacturing company that was comprised of different divisions. Each division had been its own company and was brought under the parent umbrella. The project was to unite their communications infrastructure. In the beginning I was unaware of the "political" issues and we (the design team) were getting nowhere.

JS: I'll talk about a fairly recent one. It was small but challenging. A credit union wanted to rebrand itself from the ground up. So that entailed all new everything: company name, web site, ATM's, business cards, signage - you name it. But the biggest challenge was that the person in charge of the whole operation resigned just before I arrived. She just had not been able to get the project off the ground. So that demoralized everyone and made them feel like they may not be able to do it. But since she had floated a date to the board that was three months away, it had to be done.

My stance towards it was, "It's unfortunate that she's gone but we've gotta get it done so let's go with what we've got." The other main challenge is that there was zero PM knowledge in this organization. So I had to quickly bring the cross-functional team up to speed all the while mentoring a junior PM (really a trainer of software). My attitude is always that people are intelligent and will rise to the occasion. So we held a one-day session and I introduced them to scheduling. After some initial expected resistance, they fairly quickly warmed to the task.

After several intense sessions of scheduling and risk, everybody stepped up to the plate. One woman from marketing especially took a firm leadership role. I showed the junior PM how to run a status meeting and then transitioned over to her. And I'm pleased to say that when I logged onto their old web site on the "go-live" day, it instantly clicked over to the new one. All systems go, right on time. And in recently speaking to the manager, they have been incorporating some of the best practices in subsequent projects. They don't need my services any more, which is exactly how it should be.

GR: Nondisclosure agreements prevent me from discussing my most challenging project. However I can tell you about one of my most challenging projects I managed in military.

During my tenure as the chief technician, specifically in 1985, the U.S. Department of Energy provided my unit with $400,000 worth of solar photo-voltaic electrical systems to test the viability of solar powered electrical generation, which was to serve as a backup power source for the radio gear. We selected 14 different sites, stretching from McMurdo Station, located on Antarctica, to Adak, Alaska, as well as many of our island locations in the Pacific, including Hawaii, Midway, Okinawa, Guam, and others. These sites were operated by trained operators as a collateral duty, separate from the daily construction activities of the Seabee battalions, detachments and teams.

Logistics and coordination alone were challenging. Not only did we have to get the equipment on site safely and intact, we had to ensure the systems were set up correctly, allowed enough pre-charge time, and connected to the gear correctly. Each system had to be oriented exactly due South, +/ - 1° to gain maximum sun exposure.

Data collection took more than a year. We collected information regarding recharge time under varying cloud conditions, wattage usage under various conditions, endurance testing, depth of discharge cycles, and total number of recharge cycles before the batteries would be considered useless. Unfortunately, battery technology in the mid-1980s was not what it is today. This means we were using wet cell technology rather than the lithium-ion technology we have today.

The biggest challenge I faced as PM was getting the team to work together as a team since, in essence, we were a virtual team. Bear in mind that this was 1985: the Internet was not what it is today. Our communication was solely through ham radio gear. Only a few people on the team had ever met face-to-face prior to this project. As a team building process, I asked each team member at each location to get a head and shoulders photo of themselves and make 13 copies. I then asked those copies to be sent to each of the 13 other sites. For the first 30 days of the project I got a commitment from the entire team to turn to the photo of the individual who was talking on the radio.

I was amazed at the outcome of this one process. In 1986, when the project was completed, all team members were flown to the base where I was located for a final closeout meeting. When people on the team began walking in the door, including those that had never met face-to-face, it was as if they had been working face-to-face the entire time. They began asking each other about each other's family, talking about common hobbies, and other subjects as if they had been working side-by-side for the entire 18 months.

While I would like to take sole credit for the photo idea making them a better team, I can't because they were the ones that actually did. My idea was just a catalyst.

PMA: And that's the point of successful project management: creating a system or process that is self-sufficient and useful to a company. Don't you agree? Well, gentlemen, we thank you for your time. Your insights are greatly appreciated.

This concludes our 3-part interview series.

New Horizons

New Horizons

Project Management Academy

Project Management Academy

Six Sigma Online

Six Sigma Online

TCM Security

TCM Security

TRACOM

TRACOM

Velopi

Velopi

Watermark Learning

Watermark Learning

Login

Login

New Horizons

New Horizons

Project Management Academy

Project Management Academy

Velopi

Velopi

Six Sigma Online

Six Sigma Online

TCM Security

TCM Security

TRACOM

TRACOM

Watermark Learning

Watermark Learning